Philip Giordano is not an unknown name in China. Many of his books are translated into Chinese and available to local readers. He has also come several times, and always with exciting projects, like revamping a whole shopping centre in Chengdu or drawing gigantic murals at the Duoyunxuan Art Museum in Shanghai.

Philip Giordano is one of the five illustration specialists who have accepted to be part of the 2020 Golden Pinwheel Young Illustrators Competition Jury. He will therefore be with us in Shanghai next November with plenty to tell about his distinctive books and fascinating backgrounds. If this is too long a wait, here is a sneak peek to make you wait until the CCBF great get-together…

Your life and career are marked by a fascinating mix of Western and Asian cultures. How do you manage those influences in your work? Is there a conscious process to blend elements from here and there? As an observer of what is happening in both sides of the world, do you think there is something specific that defines Asian illustration?

My mother is Filipino and my father Swiss. They come from two countries that are really far apart each other and very different. As a child I spent summers in the Alps, I was in love with the mountains, their special flowers, the misty colours, the greys of the rocks, the angular shapes. Then as a teenager I was curious to know my mother's country. We started spending winter holidays in the Philippines and my passion for the sea began with tropical landscapes, strong colours and bizarre sinuous shapes, which can only be seen when one gets close to the Equator. My roots are in both these two realities and obviously also in my country of origin, Italy: what a mess!

We are used to seeing East and West opposed and surely (that's the beauty) their inhabitants have a very different way of seeing and facing life. I see the same also in my multi-ethnic family. I try to make these differences coexist, to put them in communication; and see them as a resource, not only as an obstacle, a conflict.

I also have this attitude in my work. There are elements, techniques or colour palettes that I take from very distant cultures I came into contact with for several reasons, including Japan where I have been spending time for seven years. I mix them until I find the right formal balance. I like to mix everything, take things from different backgrounds and make it a great minestrone. Because that's what I am.

It is a kind of challenge, the result is not always satisfactory, but it seems the only possible way, at least for me right now.

When it comes to Asian illustration, I generally notice a great contamination of styles. It is no longer so easy to distinguish an Asian illustrator from a Western one, and many Asian illustrators now live in the West, so what defines an Asian illustrator from a Western one? Perhaps it is time to concentrate more on contents, on new ways of narrating this increasingly complex and contradictory reality of ours. We need new stories that help us to understand the world, wherever they come from.

Playtime Tokyo winter fair

Recently, you have started book projects for very young children. As you may know, the next CCBF will cast light on early education and toddlers’ books. How did you get interested in creating for this specific age range? What do you think is specific to them? Do they present specific challenges to the picture book maker?

Publishers started to offer me toddler book projects because I think they consider my geometric and essential style as a suitable blend for transmitting contents for the little ones.I learned that the images contained in the toddlers’ book in general have to be easy to read, immediate, and above all faithful to what they represent. A fish must have the appearance of a fish and be recognizable as such.

Children learn progressively to assimilate and recognise their environment, and book can be a valid tool in this undertaking as the pages reflect the world that the child observes and begins to experience. It helps him to position himself inside the reality and give a name to things.

Usually, books for the little ones are very didactic, and perhaps it is the right way to do them, but I think it is still possible to provide less obvious variations and describe a world that despite being the real one represents a more personal version of it.

For example, in the board book series I created for the Italian publisher Topipittori.

The writer and I tried to tell what is happening in the reality, using an uncommon vocabulary and unusual colours. Our attempt was to avoid caging the child in an adult-created stereotype of the world—the sky in which a swallow flies does not necessarily have to be blue. In the sea there are not only swimming fishes but also jellyfishes, hermit crabs, corals and other unusual creatures.

From a source the water comes out singing, not simply bubbling.

In this series we have tried, through small strange details, to tell the world in a slightly less canonical way, and the result we obtained has something unpredictably poetic, I think.

You are also an author of “non-fiction” books for children? Could you describe your creative process in the popular science field (from selecting topics to determining the style and concept)?

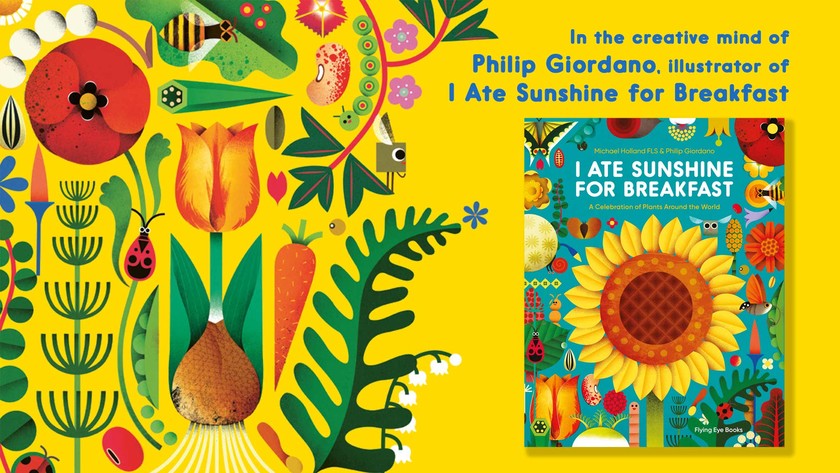

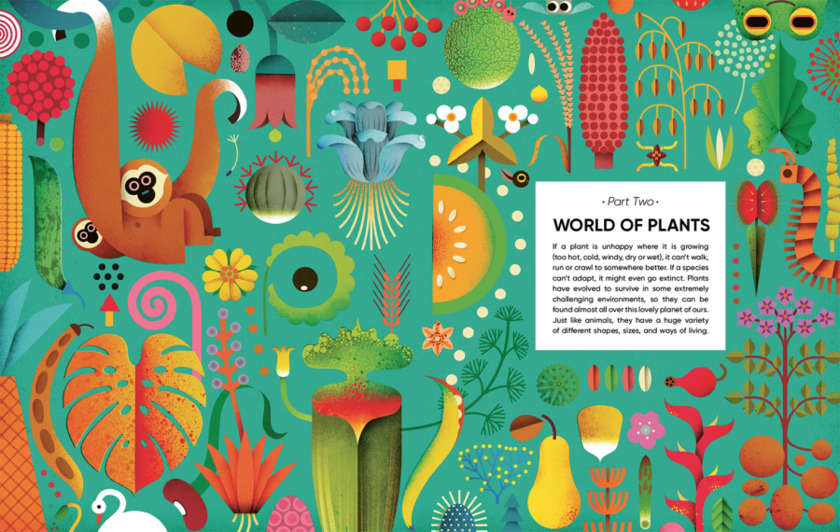

I ate sunshine for breakfast, which was just published by Flying Eye Book earlier this year, is my first non-fiction book with scientific content—114 illustrated pages full of scientific knowledge! I had never done a book dedicated exclusively to plants, it was a brand new experience for me, in terms of the approach to non-fiction and the enormous amount of work I had to achieve in a limited time. It was a bit overwhelming, but also very exciting, as I fortunately got to work with an excellent team of designer and art directors.

I Ate Sunshine for Breakfast, © 2020 Philip Giordano, Flying Eye Books

The main challenge was to create scientific illustrations while maintaining my geometric, abstract, colourful and surreal style. I hope I managed a good balance amongst all these elements. To introduce the world of plants to children, I created a quirky group of humanised insect characters led by "Little Square”, a square-shaped fly that appear throughout the book.

Is there one picture book that has marked and influenced you in the long term? And why?

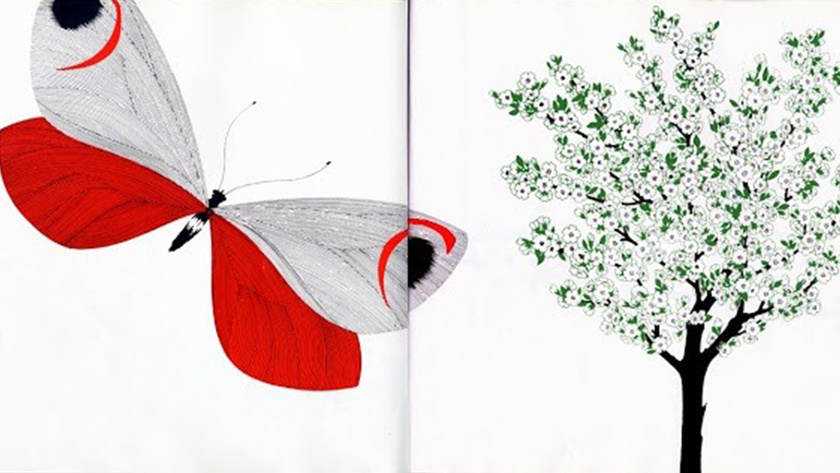

The first book that caught my attention at the kindergarten was La mela e la farfalla by Iela and Enzo Mari, an Italian designer duo. I consider it my first lesson of storytelling and design (each single image is shaped like a piece of design). It is a silent book that tells the story of a small caterpillar on a large apple tree. Page after page the little caterpillar grows and becomes a butterfly.

I identified myself with that little creature lost in a giant world made of sparkling green leaves and red apple-shaped planets. The illustrations, though simple and synthetic, are also realistic and easily readable—just enough to catch my fantasy!

La mela e la farfalla, © 1969, Iela et Enzo Mari, © 2004, l'école des loisirs for the World Rights