In June 2021, the International Institute for Children’s Literature (Osaka) revealed the winner of the 18th Brothers Grimm Award—Prof Zhu Ziqiang of the Ocean University of China College of Liberal Arts, Journalism and Communication. The prize confirms his status as a leading figure in children’s literature studies in China. Zhu Ziqiang not only pushed forward academic research on picture books and education, but he also contributed to promoting Chinese children’s literature abroad and vice versa. The Shanghai International Children’s Book Fair is deeply honoured to count on him as one of the judges in the 2021 Golden Pinwheel Young Illustrators Competition. On this occasion, we interviewed Prof Zhu about the origins of his passion for picture books, his years in Japan and his understanding of visual storytelling.

Q=China Shanghai International Children's Book Fair (CCBF) A=Zhu Ziqiang

Q: You have researched children’s literature for many years and participated in numerous awards for children’s books and recommended book lists. In your opinion, what elements make a good set of illustrations? What is your advice to young writers of children’s books and illustrators?

A: I understand illustration works just as if they were picture books. I recently published my two-volume research called Why are picture books so good? which presents ten different perspectives on picture books. In the first chapter, called “Why are picture books so good?”, I discuss the structure of this art form and relate their quality to the interaction and symbiosis between the textual and visual elements.

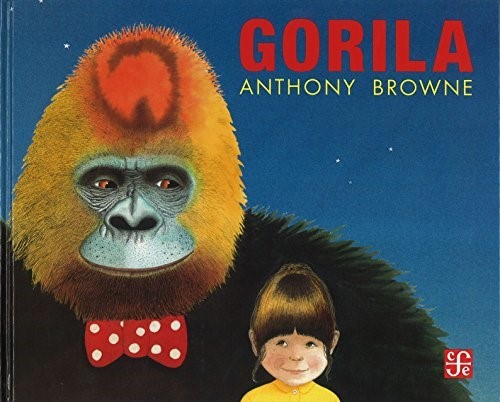

More specifically, words and pictures are understood as means of expression. Each has strengths and limitations. As much as written language appears to be more abstract and less precise, it actually offers high levels of stipulativeness and definiteness when describing abstract concepts, such as time, identity, relationships, and character’s thoughts. These linguistic resources are crucial and necessary to a rich reading experience. On the other hand, visual language can be a very concrete and evocative way of providing information, but it becomes less effective when representing certain concepts, hence needing reinforcement from the text. However, if the vagueness of visual language is used correctly, it adds a metaphorical sense to the work and turns the picture book into a genuine form of art. For example, in Gorilla, Anthony Browne tells the story of a little girl Anne and her desire to be loved by her father. In one of the illustrations, Anna sits in the corner of the room and is illuminated by the light from the TV screen. As an interpretation of this drawing, some people will say that Anna is lucky to have a television to enlighten her days. I beg to differ, as I think the screen glow is a representation of Anna’s loneliness, and the light she actually seeks is not the cold, mechanical one from the TV, but something else.

That same image gives us other hints and explanations about what she really looks for. In the background, one of Anna’s drawings is hanging on the wall—she stands next to her dad in front of the house on a sunny day. As a child, like many of you, I liked to draw… A little house, a tree by the house, some mountains in the background, and a rising sun crowning the picture. Why do we tend to draw the same kind of scenes is the result of basic human psychology: it is a way to represent our desire for a loving home. Therefore, from Anna’s drawing, we can gather that the other light she pursues is fatherly love.

Toward the end of the story, Anna’s father remembers her birthday and takes her to the zoo. As he leads Anna by the hand, their shadows on the wall indicate that he is walking with her towards the sun, meaning that Anna is finally basking under the sunshine of her father’s love.

In comparison, the kitchen in Anna’s house is filled with checkered patterns, like the gorillas in the zoo whose cages are also “checkered”. The pattern becomes a symbol of oppression. As pretty as the kitchen may look, Anna and her dad look unhappy there, and we can sense the absence of communication between them, embodied by the newspaper that prevents Anna from seeing her father’s face. Likewise, the gorillas in square cages are captive and look unhappy even to Anna’s eyes. There is a strong metaphorical dimension in those illustrations, which turns the picture book into art. If the author had used words to express those ideas, the book would have become explanatory, and its artistic value would have been significantly reduced—picture books are the art of expression, not of explanation.

In conclusion, there is a complementary relationship between words and pictures. The most important, valuable and defining characteristic of picture books is that the strength of text complements the weaknesses of the drawing and vice versa. When the two media are used together, they support and complement each other. If this relationship is achieved, picture books become a form of incredible artistic possibilities. It could even be called omnipotent art. So, why are picture books so good? I think the main secret lies here, and all their other characteristics just derive from this.

I have two pieces of advice for young writers and illustrators of children’s books. First, read as many high-quality classics as possible. Second, pay attention and study how language and pictures can express emotions. I believe that these two things will strongly benefit their creative abilities.

Gorilla by Anthony Browne

Q: In the past thirty years, you have spent long periods of time in Japan studying and researching children’s literature. Can you tell us more about your experience there and how it impacted your career as a picture book professional? What interesting characteristics do you find in Japanese picture books?

A: Studying in Japan has had a significant impact on how I became a scholar, and I am talking about my relation to picture books. In 1987, I was studying at Tokyo Gakugei University and enrolled in a class by Prof Nemoto Masayoshi called “Literary education for children”. Nemoto used to bring a stack of picture books in a package and show them to his students. Let’s say it was my first formal introduction to picture books, about which I didn’t know much. I had read a few of them in China, but Nemoto’s course offered me a brand new perspective, and I got really intrigued by the art of picture bookmaking. From that time, I began to study picture books properly. I bought several essays by Tadashi Matsui, including What Is a Picture Book? and Looking upon Picture Books, and I also purchased a lot of children’s illustrated books. By October 1988, I joined the International Institute of Children’s Literature in Osaka to conduct two months of research. I also used my spare time to help at the Seifu community library, a family-owned library run by Lady Adachi, who provided me with housing and food while I gave adults training about picture books and continued my research. This set of experiences showed me the charms that picture books retain on both adults and children.

When I returned to China a couple of months later, I brought many boxes of books back with me, including a couple hundred from Western countries or Japan and many worldly renown classics. Those books of my collection are extensively featured in the “International Children’s Books” chapter of the essay Five Voices About Chinese Children’s Literature. Shortly after my return, I also eagerly wanted to translate and publish some of these amazing works. I translated The Rabbits’ Wedding; The Giving Tree; In the Forest; Little Blue and Little Yellow, among other classic picture books. I submitted my translations to multiple publishers in Changchun and Shenyang. Although most editors recognised the quality of the books, some gave up because of high printing costs and the lack of an active market. Others suggested compressing four pictures on one page, an idea I completely rejected. Looking at how easily picture books are published in China today, I realise that innovation relies in many aspects on the stage of development of the society.

At the beginning of the 1990s, I started teaching children’s literature, with a strong focus on picture books, to both undergraduates and graduate students at Northeast Normal University. Also, as I often read these Japanese picture books with my son, his great satisfaction made me want to share those books with more children. In the spring of 1989, I held readings at a kindergarten associated with the Northeast Normal University. I might have been the first person to read picture book stories to children in China. Actually, when I was in Japan, I also used to read Chinese-themed picture books—including The King and the Five Brothers and Su He’s White Horse—to the Japanese children visiting the Seifu library.

I think that Japanese picture books are some of the best in the world. They are outstanding from all perspectives, especially in how they ingeniously combine stories and drawings. They cleverly represent the lives of children, their thought processes, and their joy. They also are visually very imaginative and humourous.

Q: You work in multiple positions not only are you a scholar, a professor, but also a writer and translator. How do you regard these jobs? How do they relate to one another or influence you?

A: I am primarily a scholar and a children’s literature researcher. This is my most important role and what matters to me the most. I recently received the International Grimm Award, which, along with the Hans Christian Andersen Award, is regarded as the highest honour in international children’s literature. Unlike the Hans Christian Andersen Award that encourages the creation of children’s books, the International Brothers Grimm Award focuses on academia and aims to award the best children’s literature scholars around the world. I consider this award a firm approval of my forty years of studies in children’s literature.

I also translate Japanese children’s literature and Japanese picture books, not only as part of my research but also as a means to push forward the publication of high-quality reading materials for children. As for my own writing, I write picture book stories not only to express my thoughts on children’s growth and experiences in life but also to prove that my theories about children’s literature are valid and applicable. I am glad to see that, in addition to winning important awards and being recognised by professionals, my works are liked by young readers.

Q: Why is it so important to understand the artistic value of picture books? In China, how can we improve the art of picture books?

A: In my understanding, the artistic value of picture books relies on their literature, as well as on the design of the drawings and the combination of the two things. As I mentioned above, the text and art have to complement each other. How can we achieve this? By designing the book well. In Overview on Children’s Literature, I explain my definition of a picture book—a holistic form of artistic design. Many world-class picture book masters are not properly illustrations or fine artists but designers.

I think that to master the art of picture bookmaking, the authors who are primarily fine artists have to focus on two things. First, they need to work on their ability to grasp the meaning, feelings and creative possibilities offered by literature; second, they should learn to use their sense of design to illustrate ideas and concepts. Let’s take an example.

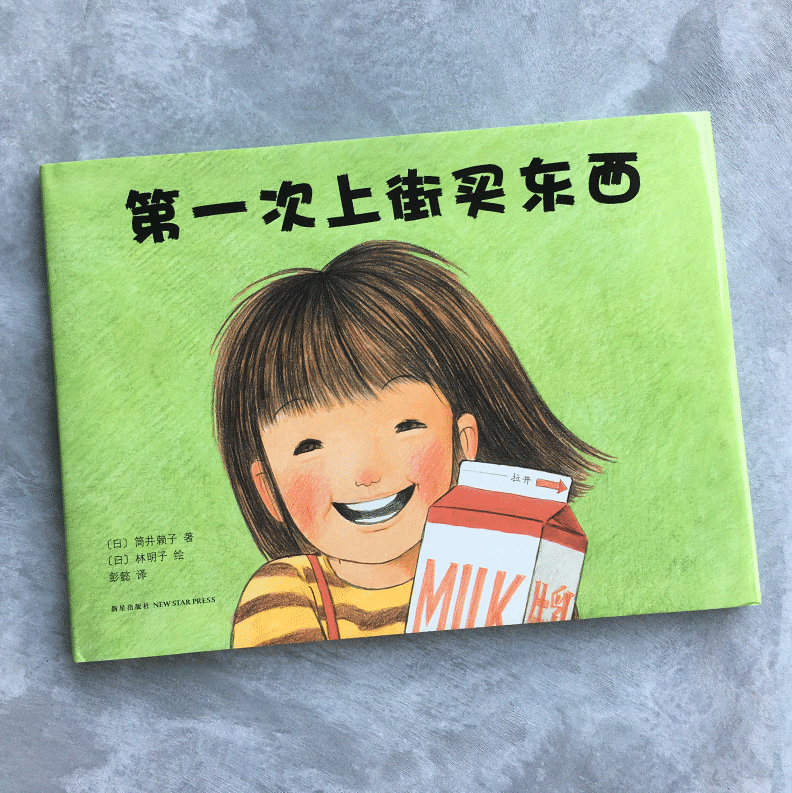

Miki’s First Errand is a story that describes in detail a child’s thoughts and actions. This type of story requires a high level of expertise and a thorough understanding of children’s mental processes and habits. But in addition to the well-written story of this book, it is worth asking whether the pictures entail a literary dimension? My answer is yes, they do. The book Miki’s First Errand shows the author’s skills in representing ideas through pictures. Miki has conquered many hardships and finally accomplished her mission—she brought milk back home for her baby sister. The back cover illustration provides a world of information and serves as a strong finish to the entire story. In the drawing, the mother feeds the baby while Miki stands at her side drinking milk, her injured knees bandaged. This simple scene contains Akiko Hayashi’s unique take on children’s psyche.

Miki’s First Errand by Yoriko Tsutsui and Akiko Hayashi

As Miki went running errands by herself, she had to overcome many difficulties. Her mother is proud, and so is she. But the eagerness and satisfaction to have succeeded just like a grown-up is only one part of Miki’s happiness. On the other side, she obtains affection from her mother, illustrated in the back cover art. Akiko Hayashi’s uniqueness lies in the dual perspective she gives of children’s development. Miki is growing to become more independent, but she doesn’t forget her reliance on her mother. By showing the children’s complex minds, the story allows children to relate to it. Illustrations so well designed are full of literature—like textures.