Luo Ling won the favour of judges as she received the 2020 Golden Pinwheel Young Illustrators Grand Award (China), rewarding her distinctive artistic skilfulness and creative talent.

We were pleased to interview our winner and hear her talk about her research and creative experiences in a variety of cultural contexts.

Luo Ling

Q&A

Q: How did you feel after winning the Golden Pinwheel Grand Award? What is the story behind Three Friends, the work that owed you this distinction?

A: First I felt very happy that my work was selected as finalist, and the award itself came as a big surprise.

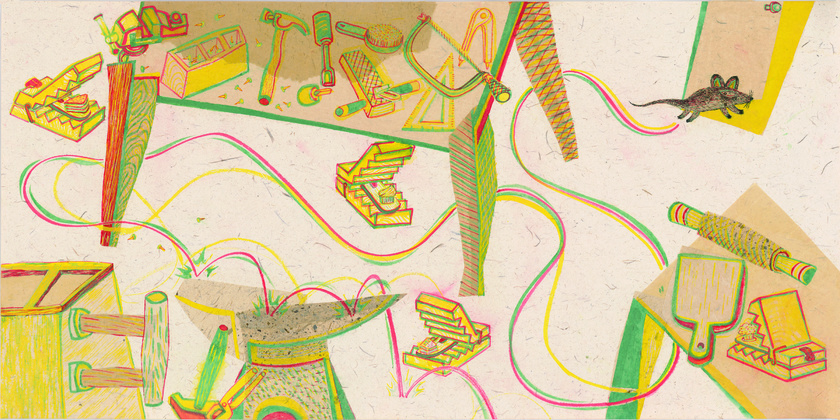

My illustrations are based on a text by children’s writer Liu Haiqi. It is a story with a strong folk flavour. The author's writing shows a great sense of humour with a patent personal charm and good rhythm. The picture book has been published earlier this month (May 2021).

Good literature results attractive to me as it stimulates my creativity. As I was studying and assimilating Liu Haiqi’s text, I felt that it encompassed a kind of allegory of our contemporary society expressed in a humorous language. Therefore, I wanted to break through my usual traditional Chinese painting style and use a more modern visual language instead.

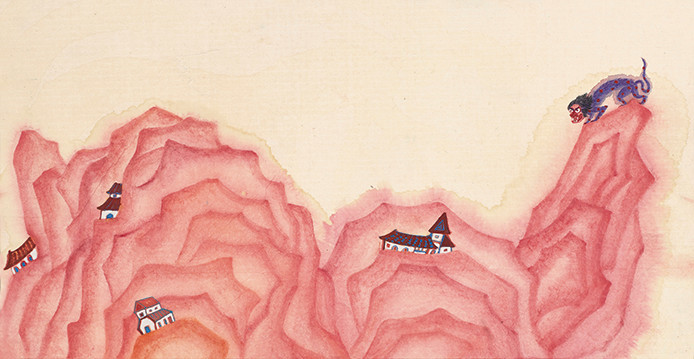

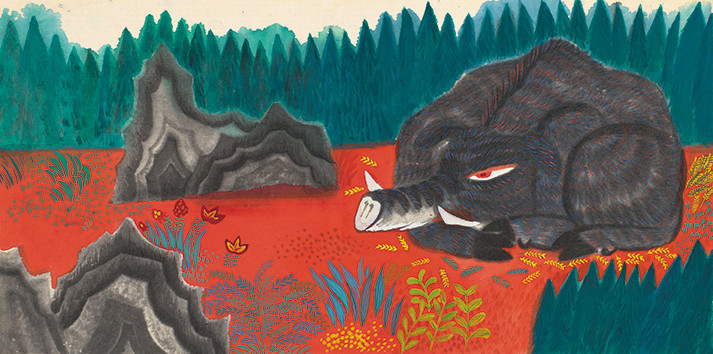

I was in Dunhuang at that time and absolutely mesmerised by the culture of the Northern Dynasties [386 A.D.-581 A.D.] and the Five Dynasties [907 A.D.-960 A.D.]. When I closed my eyes, I saw only bodhisattvas and heavenly characters. Until one day, after studying and visiting the Dunhuang caves for several days, I had an epiphany: why not use the same colouring methods as those shown in the caves? To create this set of works, I tried to come up with a limited chromatic palette. I structured the pictures around three colours assembled through collage. I elaborated my own mineral pigments, and the stone green brings some elegance to the pictures. I often make collage with rice paper and vellum, as those materials are very convenient to use, and I find the texture of Chinese rice paper absolutely unique. When you set out on a journey, even though the destination is unknown, each step brings you closer to it. After repeated attempts and several crises, the final tone of Three Friends eventually eventually took shape. Maybe it is not to everyone’s taste, but for me at least, the result does not feel platitudinous at all. This exploration has provided a new experience to my personal creative possibilities.

Three Friends, ©Luo Ling, ©Tomorrow Publishing House, 2021

Q: You studied at the Dunhuang Research Academy from 2017 to 2019. What was your purpose there and what did come out of this wonderful experience?

A: Located in Northwest China, Dunhuang was once a major urban centre. Its famous Mogao caves were built 1,655 years ago and boast 45,000 square meters of uninterrupted mural paintings. In these paintings, we can see not only the gathering of various civilisations, but also the evolution of Chinese mural tradition. Analysing the paintings allowed me to pull all the pieces of the puzzle together and acquire a comprehensive set of knowledge about Chinese mural painting. This was the theme of my graduation research. I got a fantastic chance to be in contact with these silent yet informative masterpieces.

Looking at ancient Dunhuang, I can see today’s Shanghai—a city of compound cultural influences. Today, cultural exchange between China and the West is at its peak. In such context, the coherence of knowledge structures and experience can easily fall apart, cultures gets more complex but can lose their profoundness. If one remains on the surface of knowledge, they will only reach superficial results.

Learning about the Dunhuang cave art required a full understanding of its culture. Life in Dunhuang was completely different from the life I knew in Shanghai. So, to truly understand the living conditions endowed by this far-away place, I couldn’t just be a traveller. I knew that I had to put down my luggage and open myself up if I wanted to embrace fully the land and its culture. I liked to confront my observations with what I had read in books. When I sensed a deviation, it would trigger my independent thinking.

The lifestyle of Dunhuang makes people calm and resilient. So, at a very different level, my experience in Dunhuang has also influenced my life habits. For example, every time I miss being there, I go to eat beef noodles.

Q: Many of your works are inspired by ancient Chinese paintings. How do you convey your ideas and concepts through your works?

A: Just like there is soil under every tree, everyone comes with their own cultural background. As we live in an era of cultural integration and juxtaposition, art will also have such attributes. Good art is timeless. It overcomes the borders of the context it arises from. For example, ancient art can be quite forward-looking. But the creative act belongs to the present, so it somehow reveals the current state of mind of the artist, which is an amalgam of personal attributes and socio-cultural elements proper of a time and a place. Therefore, everyone should just be themselves and allow things to happen naturally.

Q: What else inspires you to create?

A: Music, travel, observation, and research. Living a fulfilling life.

Q: You are an academic researcher as well as an artist. This summer, you will complete your PhD at the Shanghai Academy of Fine Arts. How does the study of art theory help and influence your creation? What are your career plans?

A: Sometimes artworks are the visual expression of theories, sometimes theories are the literalisation of experience. As a researcher and a creator, I think that theoretical research consists in the mirroring between intellectual and practical experiences, it is a process of mutual confirmation between rationality and sensibility. Through this process, the theoretical experience verified empirically will not be a castle in the air, and perceptual experiences will grow solid roots. Knowledge and action supplement each other and move forward hand in hand. Creativity is not altered.

Q: In recent days, China has been paying more attention to aesthetic education. You also have experience in children's art education. Can you tell us about the educational methods you use with children?

A: First, I think that aesthetic education is different from art education. Aesthetic education is our genuine reaction to the world that surrounds us. Works of art and our reaction to them are the externalisation and materialisation of this aesthetic sensibility. Secondly, when it comes to aesthetic education, guiding and cultivating are more important than learning and teaching. Lastly, aesthetic education depends a lot on our own dispositions towards art, whether we are a child or a teacher.

Keeping all the above in mind, I have set up well-received courses to introduce children to picture book making and to Dunhuang artistic heritage. Stimulating children’s creativity is at the core of my practice of aesthetic education. To my surprise, after the class was over, my students were eager to continue. I think they really enjoyed the classes.

Q: In your own creative experience, how do you perceive the difference between digital and analogical techniques in illustration?

A: The dilemma between digital and traditional techniques didn’t exist before computers were invented. This is very epochal. Book illustration is one of many forms of pictorial expression, whose visual information is read by the viewer’s eyeballs. Digital illustration can successfully transmit the information conveyed by the image, so there are many wonderful digital illustrators in our days. When it comes to the aspect of an illustration, I see a new inflexion. The "eyeball experience” is only one aspect in the development of a visual experience, yet it is not the only one. Some creators consider the mere eyeball experience cannot fully satisfy the complexity of the human beings’ sensorial interactions. Therefore, like most artists, I still like to work in a traditional way.

©Luo Ling

Luo Ling (Shanghai, China, 1981) started illustrating as early as 1999. From the beginning she developed an interest in experimenting with different media and techniques. After graduating from university, she worked as a creative researcher and designer in different fields, including mobile gaming, animation, film, television, and merchandising. In 2010, she resigned from her position and settled down in Dunhuang, where she turned to brush and rice paper as her main creative media. In 2013, she went back to university to study the theory of Chinese painting under the guidance of Professors Wang Mengqi and Liu Jian. Simultaneously, she participated in several exhibitions in China and abroad. In 2012, she was awarded the Medal of Honour of Sorbonne University in Paris. In 2015, she was shortlisted for the Bologna Illustrators Exhibition. From each of these endeavours she has acquired extensive experience and knowledge.